"Know Your Town"

“Know your Town” stories are presented by the Enfield Heritage Commission. Here we’ll bring you a bit of insight into the origins of street names or places you see every day.

The "Angel life" and the Demise of the Enfield's Shakers

Baltic Street

Caleb Dyer Lane

The Currier Family in Enfield

Enfield Center School House

Enfield's Fire Department

Enfield’s Shaker Museum Meets the Challenge of a New Century

The Roads of George Hill

High Street

Home in Enfield

Huse Park

Interstate 89

Jones Hill

Know Your Heritage Commission

Livingstone Lodge

Lockehaven Road

Main Street

Native Americans - Enfield

A New Chapter at the Heritage Commission

NH Route 4A

Old Home Days and Certified Local Government Follow Up

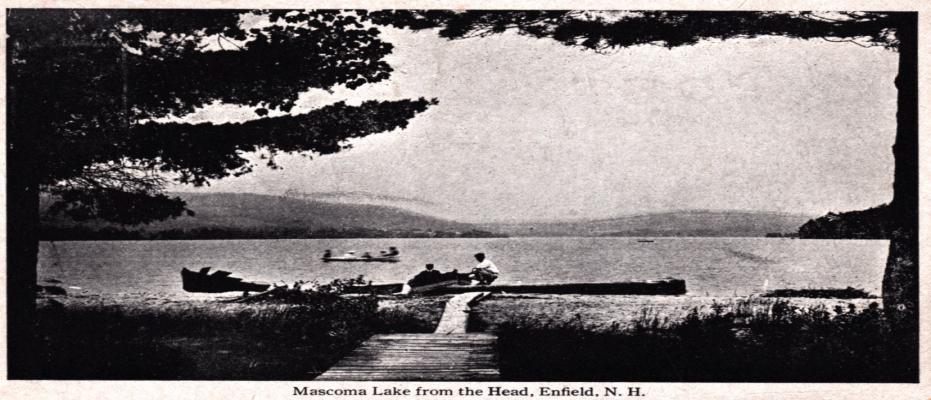

One Hundred Years of the Mascoma Lake Association

Railroad House

Shady Dealings in Enfield

Shaker Boulevard

Shaker Hill Road, from Main Street to the split with Livingstone Lodge Road

Town House

The Union Church at Enfield Center

Wells Street

Whitney Hall

Water - Enfield's Multipurpose Gift

Lockehaven Road

Lockehaven Road -- For a quiet town in New Hampshire, Enfield’s urban development has been surprisingly dynamic. Since the area was first divided and transferred under British rule, Enfield has seen its centers of population, commerce and names change several times. Smaller Enfield Center was once a busier commercial area than today’s downtown, which was once known as North Enfield. West and East Enfield are names that mean little to today’s Enfield residents. And who recognizes Chebacco Street?

Chebacco, Chebacco Street and East Enfield are what we now call Lockehaven and the eastern part of Lockehaven Road. Likewise, the body of water associated with this area of Enfield has been called Deep Lake, Johnson’s Pond, East Pond and now Crystal Lake. The name “Chebacco” came with settlers from Massachusetts, while “Lockehaven” honored Edwin E. Locke, who purchased a homestead that belonged to the Johnson family in 1885.

Locke’s first sight of the property was inauspicious. He arrived by open sleigh in the winter and, having left a lantern in Canaan, saw the property only by the light of matches. Nevertheless, the location near the snow-covered East Pond was appealing and Locke signed for the property. In April Locke finally took possession of his new home in East Enfield after braving the mud of West Canaan Road—now called Mud Pond Road.

Locke became such a prominent member of his new community that when residents decided they were “not satisfied with all places adjoining Enfield being identified only by points on the compass”, they adopted the more romantic name of “Lockehaven” with “Main Road” becoming Lockehaven Road.

Lockehaven had a Post Office located in Edwin Locke's home. The office was established in 1891 and Locke was the first postmaster.

Next door to Locke’s home was a meeting house in disrepair, which he bought. Locke had the steeple removed (school was suspended so children could watch the operation) and the building was converted into a popular venue for concerts, parties and dances. Although Locke’s plays have faded from memory, his granddaughter recalled one play that was set in Montana and written at the request of Frank James, the brother of bandit Jesse James. Frank James proposed coming to visit and see the play, but Locke’s wife made sure no invitation ever reached the notorious bank robber’s brother. Who knew that our visits to the transfer station on Lockehaven Road connect Enfield residents to a piece of the Wild West?

Sources: Enfield New Hampshire 1761-2000. The History of a Town Influenced by the Shakers. Ed. Nancy Blanchard Sanborn.

Marjorie Carr, Town Historian

Back to Top

Main Street

Main Street -- Like several other things in our town, Enfield’s Main Street owes its development to the Shakers and their dynamic leader Caleb Dyer. In 1847 Dyer convinced the Great Northern Railroad to change its plan for its route between Concord and White River Junction. Instead of following the western side of Lake Mascoma (the 4A corridor), it would pass through a cluster of houses and mills known as North Enfield. This kept the landscape and Shaker settlements on the lake’s eastern shore from being disturbed but forced the Shakers to take a five-mile journey around the lake to reach the North Enfield railroad depot and businesses. Dyer led construction of the “Shaker bridge” across the narrow part of the lake in 1848. With three more bridges across the Mascoma River by 1849, the area between the Shaker bridge and the Canaan road (Route 4) became the economic center of the Enfield township.

North Enfield became known as “downtown” and its busy Main Street boomed. By the end of the 1800s, Main Street had mills, churches, hotels, blacksmith’s shops, grocery shops, hardware, a jewelry store, an undertaker, a post office, carriage and harness shops. Forty houses were built in 1893 alone. In 1897 land was donated for Huse Park and the imposing Copeland block was built. The library was completed in 1901.

It did not last long. Decline began with the 1929 Crash and the Depression. Mills on the river and other businesses closed, leaving today’s gaps. With foot traffic gone, cars took over.

Dolores Struckhoff, whose family owned a hotel on the site of George’s grocery, remembers the early 1960s when Main Street was a “living breathing community with two grocery stores, Fogg's Hardware Store, Billy's (the local five and dime), the post office, Lucien's drug store, and the grain store.” The sidewalks were filled with people, “running errands, greeting each other, stopping for chats, going about their lives as gas men, electricians, plumbers, painters, railroad employees, mill employees, grocers, postmen, pharmacist, clerks, waitresses, doctors, nurses, secretaries, teachers, or taking part in their hobbies around the river and lake.” Since 2000, the Enfield Village Association has been working with New Hampshire’s Main Street program to beautify and return to Enfield’s Main Street to its former vitality.

Source: Dolores Struckhoff, Enfield New Hampshire 1761-2000. The History of a Town Influenced by the Shakers. Ed. Nancy Blanchard Sanborn.

Back to Top

Wells Street

Wells Street -- Many thanks to John Carr who researched and wrote this edition of “Know Your Town”.

Wells Street is in the residential area located above Enfield’s main street and the original Northern Railroad corridor that follows the Mascoma River. The Wells Street neighborhood was developed near the close of the Civil War from a nine-acre tract belonging to Henry Stevens.

In March 1868 this tract was sold to Francis H. Wells, a Canaan farmer, for $900. Wells divided the tract into lots of about one-half acre each, reserving a double lot where he built the street’s first house for himself. In 1869 Enfield’s selectmen approved a petition to lay a road—designated Wells Street—on Wells’ property and to compensate him for the right-of-way.

Sylvester Cross, a noted builder of the day, built the home for Francis Wells, which is now on the Historic Register. With its rich architectural decoration of pilasters, cornices and pyramidal hip roof and original Enfield granite posts, the Wells house is a prime example of Italianate Colonial Revival style.

Several other homes were built on these Wells Street lots between 1870 and 1900. Today, Wells Street has several of Enfield’s classic original homes unaltered from their original appearance. One of these is Wilson House, a two-family dwelling built in 1894 whose Victorian colors show off its original design and twin porches.

Another house built by or for Eugene A. Wells in 1895 features many elements of the Queen Anne style. Its picturesque roofline, cross gable with cutaway corners and fine decorative trim makes this house one of the premiere Victorian buildings in Enfield.

Wells Street also claims heritage to two multi-family Shaker dwellings that were moved to their present location from the Shaker community on the West side of Mascoma Lake.

Wells Street, which does not have an outlet, terminates with a commanding view of Mascoma Lake and the mountains beyond. Its concentration of original buildings and older homes give viewers a glimpse of how Enfield looked in the 1800’s.

JPCarr 2-2021

Back to Top

Shaker Hill Road, from Main Street to the split with Livingstone Lodge Road

Shaker Hill Road, from Main Street to the split with Livingstone Lodge Road -- Like many things in the history of Enfield, the name of Shaker Hill Road is neither as simple nor obvious as it seems at first sight. It does climb the hill whose name reflects the fact that it was where Enfield’s first Shakers congregated in the 1780s.

However, the Shakers moved from that area in the 1790s and for most of its history the artery that runs between Main Street and Shaker Hill was known as “South Street”.

While the Shakers gave the hill its name, the area owes its current character to its years as the heart of Enfield’s industry. It is hard to imagine now, but this stretch of the Mascoma River teemed with dams that produced power for mills that ground flour, sawed lumber, pressed cider, made bedsteads and eventually worked wool.

The first mill was built in the 1770s near the site of the Copeland Block. Several others would follow, clustered around the current intersection of Main Street and Shaker Hill Road. Bridges were built across the Mascoma, including the Shaker Hill Road one built in 1789, linking the mills to the growing road network. Although the Shakers had moved to Mascoma Lake’s western shore, they owned many of the mill buildings that they leased to operators.

By the 1880s, most of the mills were involved in wool processing, including dying, spinning and weaving. The American Woolen Co. mill on Baltic Street alone employed up to 375 people in the 1950s.

The housing needed for the influx of people coming to work in these flourishing businesses, many from Finland, Ireland and Canada, gave Shaker Hill Road its current character.

Between 1892 and 1907, sixty homes and tenements were built for mill workers, most in Shaker Hill Road’s side streets. Two buildings now on Wells Street were dragged across Mascoma’s ice in 1890 for tenements. Most of the distinctive Mill Houses—eight duplexes—near the intersection of Shaker Hill Road and Pillsbury Street were built in 1918 by the American Wool Company for its employees, with Mill Street behind them.

Shaker Hill Road also provided homes for the mills’ managers and owners. Number 27 Shaker Hill Road was the home of George Whitney, whose father purchased the Baltic Street mill complex in 1894. Soon after, Whitney set up poles and strung electric lights from Baltic Street to Shaker Hill Road and several other Enfield streets. A novelty at the time, Enfield’s street lights made the town an attraction for travelers. Whitney also donated generously to the Library and Memorial building that now houses Whitney Hall, the Enfield Public Library and town offices.

In 1902, Enfield finally got a Catholic church after almost a century of celebrating Mass in homes and a meeting room above Enfield’s first permanent fire station. St. Helena’s Catholic Church was built on the site of a home and a lot on 36 Shaker Hill Road. The distinctive stone of its entrance was quarried from an outcropping of unusual rock near Lebanon, rolled downhill and carried across the river to be loaded onto horse carts. It is as striking today as it must have been the day it welcomed its first parishioners over a century ago.

Back to Top

NH Route 4A

NH Route 4A -- Of course the most important street or road in our town is Route 4A, the true main artery that gave life to Enfield.

One of the most important spurs to the development of the United States as a nation in the late 1700s was the creation of privately-financed transport networks. Shareholder companies that raised money and repaid investors from tolls helped build the canals and roads that powered geographical expansion and economic development.

In 1796, New Hampshire raised money for a turnpike connecting the capital of Concord to the seaport of Portsmouth. This First New Hampshire Turnpike was repeated across the state and a Fourth Turnpike connecting Lebanon to the seacoast (via Croydon) was incorporated in 1804.1 More precisely, this turnpike ran from the east bank of the Connecticut River to the west bank of the Merrimack River.

As often happens, building what would later become Route 4A overran original estimates and ended up costing twelve dollars per mile instead of six. The route would change too. For a time, it ran northeast around Enfield center and emerged at foot of George Hill, thereby avoiding the steep hill and sharp turns east of Enfield Center. Later, the road returned to its original path, which is what we use today.2

Enfield Center, which straddled the Fourth Turnpike became a stagecoach stop where travelers could find rest and refreshment at two hotels and coaches could change horses. By 1840, Enfield Center had two stores, sawmills, shingle mill, tannery, brickyard and lock shops flanking the road. In 1840 commerce fed by the road made the Shaker settlements on Mascoma Lake’s western shore Enfield’s biggest taxpayers.3 Regular stagecoach service carried passengers and freight to Boston and Canada from Enfield Center. The cluster of buildings known as “Fishmarket” (still on some maps today) became the “nucleus of business and manufacturing in Enfield”.4 Fish from George Pond and Crystal Lake travelled along the Fourth Turnpike to Hanover, Concord, Boston and Burlington. In 1886, 200 people lived in Enfield Center; numerous residents put in sidewalks and Enfield Center was a thriving place to walk and shop. The Knox river, which crossed under 4A, powered upwards of twenty mills that ground flour, sawed wood, cut shingles and manufactured essential tack for draft horses.

The arrival of the railroad and the automobile, numerous fires and the decline of the Shaker communities all diminished Enfield Center. The township’s commercial heart moved from Enfield Center to Enfield’s Main Street area, following the railroad. Nevertheless, 4A remained the principal connection between the Hanover area and southern New Hampshire. The construction of Interstate Route 89 in the early 1970s dealt the final blow to the importance of Route 4A.

In 1925, the section of New England Route 14 running between Vermont and Andover was renumbered US Route 4. Route 4A is now considered merely an “alternate” route of US 4, a sad comedown for what was once one of the most important roads in New Hampshire.

-------------------------------------

1 Sanborn p. 155

2 Sanborn, p. 167

3 Sanborn p. 155

4 Sanborn, p. 166

Back to Top

Caleb Dyer Lane

Caleb Dyer Lane -- The greatest influence of the Shakers on the town of Enfield as we know it today was through the vision and hard work of a single man: Caleb Dyer.

A New Hampshire native, Dyer was the eldest of five children in a family that joined the Shaker community in 1813, when he was thirteen. Dyer’s mother was unsatisfied with Shaker life and left after two years; her children stayed behind. Caleb became an Assistant Deacon when he was twenty-one and began his long career interacting with “people of the world” as non-Shakers were called.

It was Dyer who made a deal, including the gift of land on the north side of Lake Mascoma and funds to buy a locomotive, to reroute the planned railroad. He convinced the railroad directors in Concord to lay tracks through north Enfield rather than along the 4A corridor, preserving the Shakers’ farms and tranquility.

This changed the balance of economic activity in the Enfield township, which the Shakers made the most of. Dyer’s work on behalf of the Shakers would coincide with both Enfield and the Shaker community’s greatest prosperity and population. Dyer was responsible for building farm and manufacturing buildings renowned in New England for their modernity. A cow barn he built was heated and silage was warmed, which increased milk production by twenty percent.

Dyer oversaw the transformation of the downtown area—then known as North Enfield—and took a personal interest in the various industries located along the Mascoma, which included a grist mill, tannery, blacksmith and a woolen mill supplied by Merino sheep the Shakers raised. All this activity called for a better connection between the Shaker community on the western side of Lake Mascoma. It was Dyer who led the building of the Shaker Bridge.

The prosperity that Dyer brought to the downtown inspired a movement to change its name to Dyersville, an accolade that was not accepted by either Dyer or the Shaker ministry. Thus, the shock must have been incalculable when a drunken man murdered Dyer in 1863. The man had come to visit his daughters and, unable to find them, shot Dyer who happened to enter the office where the man was waiting. Despite the care of local doctors, Dyer died 13 days later.

Dyer’s head for business, his personality and skill were so integral to the Shakers and the town of Enfield, that neither recovered completely from his death.

Soon after, non-Shaker businesses that Dyer had worked with took advantage of the gap left by his absence. A series of shady transactions using doctored books drained the Shakers’ funds in fraud and legal expenses.

Other factors contributed to the Shakers’ decline, including improving conditions in New England, which made communal life less attractive, the transformation from an agricultural to an industrial economy and the failure to attract new and younger members. The decline of the Shakers after Dyer’s death in 1863 ended when the last of the families was disbanded in 1923. Buildings were sold and moved and the furniture in them was sold, furnishing many homes in Enfield.

Shaker lands were put on the market. They attracted the interest of a New York sporting club and a resort. The Shakers preferred selling to the La Salette missionary order (for much less) because they preferred a religious use. After 70 years as a seminary and site for retreats, La Salette sold most of the acreage to a developer in 1985. Caleb Dyer Lane was the name given to one of the new streets in the newly subdivided land.

Back to Top

Shaker Boulevard

Shaker Boulevard -- So far, we have talked about Enfield streets and roads connected to the town’s industrial and agricultural past. Now, let’s talk about one connected to the town’s recreational past—and present; Shaker Boulevard, which serves the eastern and southern shores of Mascoma Lake.

Artifacts reveal that Native Americans camped at Mascoma Lake’s head, near what is known as Crescent Beach and the mouth of the Knox River. The camp was apparently on a native trail between the seacoast and the west, making it the precursor of the section of road that meets 4A and disused Fuller Hill Road.1

The Shakers owned most of the land around Mascoma Lake in the nineteenth century. The lake’s eastern shoreline was the “back side” of farms along Shaker Hill road, which provided access to them. Farms on the south end of the lake were accessed from a road between the 4th Turnpike (now 4A) and the Fuller Hill road, which is barely visible today as it ascends from the tight curve where Shaker Boulevard turns to hug the lake’s eastern shore.

In 1883 the Shakers gave Lebanon man, Frank Churchill, permission to build a cottage on Point Comfort, across from the current Shaker Museum. Several other cottages and a cookhouse soon followed. In 1885, W.A. Saunders opened the Lake View Hotel, located where that tight curve is. For $2 per day ($6-$10 per week), guests at the Lake View could enjoy a bowling alley, tennis court and croquet ground. A “delightfully cool” atmosphere, “freedom from mosquitoes, or any other objectionable features, beautiful location and moderate charges, render it one of the most desirable resorts in New Hampshire”.2

The farms around the Knox River were broken up and sold for cottages and eventually there was a boardwalk connecting the Lake View Hotel and this “cottage city”.

More cottages began populating the eastern shore, but the only road remained a half-mile section created for the sawmill that made boards for the new buildings from nearby trees.3 Some homeowners added private sections that were used by other residents.

The principal form of communication was by boat. From 1877, regular service was provided by a former lumber scow called the “Sallie Anne”—and various successors. Docked on the Mascoma River, just below the railroad bridge, the boatman met passengers at the train depot with a wheelbarrow for luggage.4 The boat also did the mail run, with the boatman aiming perfectly to throw mail onto residents’ docks. A white flag at the end of a dock signaled mail or passengers to pick up.

Building material was brought by boat from across the lake and several buildings were towed across the ice by “bees” of volunteers when the Shaker settlement closed in the 1920s.

For supplies, residents depended on boat deliveries from local shops or rowed across the lake to purchase produce from the Shakers. Shakers also came to homes to repair shoes and canoes. Visiting the Shaker settlement and the shop where they sold the boxes and other items they made was a favorite summer entertainment.

Children and young people remembered the days before Shaker Boulevard was built, and brought cars with it, as “paradise”.5 They could take the Sallie Anne to town for ice cream, roam the woods, visit other cottages and attend the numerous dances and activities at the hotel all by themselves.

An 1898 article in the “Lebanonian” said the “great needs” of the lake were “a highway on the east side, passing the depot to Point Comfort and a draw in the Shaker Bridge, allowing larger craft to pass”.6 The bridge became passable soon after. Only in 1937 was a “town road” built, making a complete loop from the town end of the lake to 4A. The Works Progress Administration, one of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, carried out the work.7

The current road—part paved and part gravel—owes its grandiose name to the father of Lula Moody, who baptized it “Shaker Boulevard” in 1924.

Sources: Enfield Bicentennial Committee, Mascoma Lake, 1961; Sanborn, Nancy Blanchard, Enfield New Hampshire 1761-2000. The History of a Town Influenced by the Shakers, 2006.

1 MLIA 1961, p. 81

2 MLIA 1961, p. 25

3 MLIA 1961, p. 61.

4 MLIA 1961, p. 120

5 MLIA 1961, p. 28

6 MLIA 1961, p. 23

7 MLIA 1961, p. 118

Back to Top

Interstate 89

Interstate 89 -- One of the most important roads for Enfield is one of its newest. No artery is as important as Interstate 89 for both our daily connections to jobs and errands and for reaching the world beyond the Upper Valley.

I-89 originated with President Dwight Eisenhower’s signing of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. The first Upper Valley interstate connection was I-91, which was completed in 1965. Our section of I-89, between Bow Junction and White River Junction, was completed in 1968.1

I-89 is so deeply engrained in Enfield that we probably could not imagine life any other way. But it almost was. I-89 was originally intended as a strictly north-south (designated with an odd number) road, that would split off I-95 at Norwalk, CT and extend to the Canadian border. After three years of discussion, I-89’s route was changed to link Boston and Montreal.2

There was further debate over two proposed routes for I-89: One would go from Warner, N.H. (near today’s Exit 9) and run south of Mount Sunapee to Claremont, where it would cross into Vermont and head up the Champlain Valley. The second route would go from New London through Lebanon to Montpelier and Burlington. Claremont businessmen lobbied unsuccessfully for the former. The political firepower of NH governor Lane Dwinell and U.S. Senator Norris Cotton, who were both from Lebanon, made the second choice a reality.3

The new highway’s route took advantage of existing roads, including Enfield sections of NH Route 10 and US Route 4. It followed the valley between Shaker Mountain and Methodist Hill, which is wider than the 4A corridor that serves these areas. I-89 split off a corner of Enfield known as West Enfield, which was already remote from the town’s population and commercial centers. Exits 15 and 16 were created to serve this area. In 1960 Enfield selectmen named the exits “Montcalm” and “Purmort” for the Montcalm settlement, which once had a school and post office, and a local family. The Purmort exit (14) provides access to US 4 via Eastman Hill Road. The roads reached via the Montcalm exit are dead ends and I-89’s Exit 15 is the only way out, making it an essential road.

New Hampshire residents travel an average of 2,400 miles on interstates. Upwards of 22,000 vehicles travel on I-89 between exits 14 and 17 according to the New Hampshire Department of Transportation (most recent numbers are from 2013).4

According to a 2009 federal mandate, New England states that number exits sequentially from state lines must renumber them based on mileage. This would make it possible to add or close exits without renumbering. A mileage numbering system facilitates highway work and rescue. Although Vermont has changed its signage, New Hampshire’s Governor Sununu has sworn to resist. “Exit numbers are a point of pride for some of us in NH – and we shouldn’t let Washington bureaucrats threaten to take that away!”5 DOT officials confirm that there are no plans to change Enfield’s exit numbers.

Exits are more than just a point of pride. The political support that brought I-89 and spurred development of 12A and the Lebanon-Enfield area also gave us our exits 14 through 17. We have them to thank if Enfield is not Claremont or Windsor.

1http://www.nhgoodroads.org/UploadedFiles/Files/InterstateHihgwaySystem.pdf

2https://intertropolisandrouteville.fandom.com/wiki/Interstate_89#New_Ham...

3https://www.vnews.com/Archives/2016/02/column-taylor-interstate-vn-012116

4https://www.nh.gov/dot/org/operations/traffic/tvr/locations/documents/en..., 5https://www.nh.gov/dot/org/operations/traffic/tvr/locations/documents/le...

Back to Top

Baltic Street

Baltic Street - Just as the Shakers go hand and hand with Enfield’s development, so do dams. Dams along the Knox River powered over twenty mills in Enfield Center. On the Mascoma River, dams protected Lebanon against floods and contributed to the economic development of downtown Enfield.

Four dams on the Mascoma powered Enfield’s industrial heart on Main Street: One about one thousand feet above the South Main Street Bridge, one near the Copeland Block, one above the Carl Patten Bridge between Baltic Street and Union Street and a fourth, known as the Upper Falls Dam, which crossed the Mascoma River on a stretch of Baltic Street between Route 4 and the Carl Patten Bridge.

The fourth dam powered several new activities that were served by a road now called Baltic Street. These included a Shaker sawmill, a shop that made rakes and a bedstead mill transferred from Enfield Center. At its peak, the bedstead mill employed twenty men who produced several thousand dollars’ worth of goods per month. It closed in 1882 and in 1897 the buildings burned.

After bedsteads, Baltic Street became the center of Enfield’s textile industry. On hearing of a woolen mill in Vermont that had burned down, Enfield’s selectmen contacted the mill’s owner Benjamin Greenbank with an offer to move to Enfield. The offer was sweetened with $3,200 (raised by subscription) and donations of land and water rights. Ground was broken for the new factory on Baltic Street in 1886. Schools took a half day off and the celebration was enhanced by blowing up boulders to create the new dam. The mill was completed with an impressive bell and ten sets of woolen machinery. It took two hundred men, aided by “fifty or more ladies” to raise the timbers for the structure.1

Greenbank’s mill employed many Irish and Finnish immigrants and was a commercial success. When Greenbank was forced to sell the mill, George Whitney purchased it, changing its name to the George Whitney Woolen Company. Whitney added a generator and produced electricity for the town. For a time at least, the lights of downtown Enfield were a minor tourist attraction. Whitney was generous to Enfield; his contributions for a public space in the Library Memorial Building enabled the construction of the third floor—Whitney Hall.

In 1899, Whitney sold out to the American Woolen Company, which owned several other mills in Vermont and New Hampshire. Later that year, a devastating fire caused a hundred thousand dollars in damage. The mill was repaired with remarkable speed, only to find itself buffeted by turmoil originating beyond Enfield. A strike was averted in 1902 and the Depression closed the mill until the 1930s. It would get a brief reprise during World War II. Post-war changes in the textile industry made American Woolen Mills vulnerable to the textile conglomerate Textron, which took control of the Baltic Mill in 1955. Textron closed it down in 1956.

The mill complex on Baltic Street got another chance in late December 1956. Quechee company A.G. Dewey took over when its facilities were displaced by a Connecticut River Valley flood control dam. Once again, Enfield was excited about the prospect of 375 new jobs and the revival of manufacturing. Under Dewey, the mill returned to being Enfield’s largest employer and its major economic support.

Enfield natives, like Steve Patten and Paul Currier, worked at the mill while going to school. On Sundays, during the summer or on afternoon and evening shifts, they did hard and messy jobs, such as cleaning wool off the looms or carrying boxes of heavy, wood bobbins. Patten and Currier remember heat, dirt and how Mascoma Lake took the tint of the cloth being dyed that day.

A.G. Dewey closed the mill in 1971.

Today, what remains of the mill complex on Baltic Street is a daily reminder of the industry that enriched Enfield’s economic resources, sometimes at the expense of its natural ones.

1 Enfield New Hampshire 1761-2000. The History of a Town Influenced by the Shakers. Nancy Blanchard Sanborn.

Back to Top

The Roads of George Hill

The Roads of George Hill - The area known as George Hill, which is located between the Bog Road, George Pond and the hills east of Enfield Center village, was first settled in 1798 and George Hill Road is one of Enfield’s earliest thoroughfares. From Enfield Center the road travels a mile up the hill to the height-of-land, before going another two miles to Enfield’s current town line and from there to Springfield.

George Hill road originally ran in a nearly straight line through land to the west of its current location until it joined the Fourth New Hampshire Turnpike (Route 4A) near George Pond. The road’s route was changed from its original straight line to enter the Fourth New Hampshire Turnpike at a four-way intersection with Rollins Road (Boys Camp Road). Some years later, the road’s path was changed again to pass the front of the George Hill Cemetery; this is its current location. Until the 1950s the road was unpaved and its muddy conditions in early spring caused the residents some difficulty.

George Hill Road meets the Bog Road at McDaniel Marsh, forming the western boundary of the area. Bog Road follows the hillside and returns to the Fourth New Hampshire Turnpike at George Pond.

There are a few other roads in the George Hill area. The Choate Road (Palmer Road) branches off from George Hill Road and runs about a mile and half before coming to a dead end at the site of the original Choate farm. Another road, called the Bluejay Road leads off the Choate Road; it originally ran between George Hill Road to the Fourth New Hampshire Turnpike. There were no settlements on this road, which has since been discontinued.

Another discontinued road, the Old County Road at the Springfield town line, ran over the mountain to the Bog Road. It provided access to the Whittemore farm and the Grantham Meeting House. Today’s map of Enfield shows an annex at the very southern part of George Hill. This was originally part of Grantham. Because the original landowners found travel over the mountain to Grantham inconvenient, on January 13, 1837 this section was annexed to Enfield, apparently to the great satisfaction of those who lived on that part of George Hill.

The cemetery at the foot of George Hill Road was laid out prior to 1800 and enlarged by residents who received a burial lot in exchange for their efforts. Many original settlers are buried here and a walk through the cemetery reveals their names and history. There is also the small private Adams Cemetery, which is surrounded by an iron grill-work fence and a stone inscribed “H. Adams 1861”. George Hill road was also home to one of Enfield’s first schoolhouses, established in about 1780.

George Hill Road is the site of significant farms, several dating to around 1800. Prominent among these were the farms of the Little and Edwards families, who owned large tracts of the land annexed from Grantham. Some of these original tracts still belong to descendants of the original two families; this represents seven generations of continuous ownership. Remnants of what was a significant orchard located at the beginning of the hill can be seen along the road edges. Before the forests in the area grew up, a traveler descending George Hill could see George Pond, Mascoma Lake and Crystal Lake in the distance.

The George Hill area remained basically unchanged for several decades. Although more recently it has experienced growth in private homes and population, it still holds a its place in Enfield’s early history.

John P Carr

12/09/2021

Back to Top

Jones Hill

Jones Hill - A homemade data analysis of Enfield’s topographical names reveals the influences on our town; a group (the Shakers), numerous families (the Choates, the Ibeys, etc.) and the land (hills and ponds).

This month, we’ll look at a place that combines families and geography, Jones Hill, Jones Hill Road and Kluge Road.

Jones Hill lies in what was originally known as East Enfield, part of which was renamed Lockehaven (see Enfield Town Newsletter of January, 2021).

Sometime before 1792, Moses Jones arrived in Enfield from Hopkinton, N.H., after an eventful life. During the French and Indian War, he had been captured and held long enough that his family gave him up for dead. Jones returned, but then left home again to fight in the American Revolution, staying in the military until 1779. Jones was not the first veteran to seek calm in Enfield’s beautiful setting.

When he arrived, Jones purchased land from the Shakers on the west side of Lake Mascoma. He then traded this for another piece of land on the high ridge, which is now named for him. With the trade came a house that was reached by a muddy, and rutted road—now known as Jones Hill Road. Moses Jones had two wives and six children. Later he added to his original holding, which would be divided up over the several generations of descendants who farmed the rocky ridge. In 1855 there were about a dozen families on Jones Hill, who eked out a living from sheep, cows, chickens and vegetables.

When Jones moved to the hill that bears his name, several Shaker families had been living there since the 1780s. After the trade, they joined their coreligionists in settlements on the lake’s western shore.

Lockehaven Road splits the road that connects Jones Hill Road to Shaker Hill. The section to the west was first known as the Jones Hill Road extension until being renamed Kluge Road, in recognition of another family with close ties to the lower part of Jones Hill.

Kluges have a multi-generational connection with the tourists that have been attracted to the Mascoma lake area since the early 1800s. In 1953, the parents of Enfield selectman John Kluge bought an inn on Sunset Hill. Until the 1980s, Kluge’s Inn on Sunrise Hill served three meals a day to around fifty guests. With the death of the elder Kluges and competing obligations, the younger generation ran the inn as a bed and breakfast before eventually closing it.

Today the former inn has new life as Visions for Creative Housing Solutions, which provides full-time housing and care for adults with developmental disabilities and similar disabling conditions. Founded by Sylvia Kluge Dow, her husband David Dow and other families, Visions is an Upper Valley (and beyond) innovator, which has expanded to provide its “wraparound” care in Lebanon and Hanover.

One of Enfield’s oldest cemeteries and its newest one are both on Jones Hill. The Town Cemetery, which is on the Crystal Lake side of the hill, opened in at least the 1790s. Countryside Cemetery, which still has lots for sale, is on the Kluge Road side of the hill.

While not the highest point in Enfield, Jones Hill is certainly one of the most easily accessible and panoramic ones. Whether it is of Canaan’s hills white with winter snow or gilded with fall leaves, the view from Jones Hill Road’s highest point is one that should make anyone happy to live in Enfield.

Back to Top

High Street

High Street - When the British refer to the “high street”, they mean the equivalent of our American “main street”, the commercial and social heart of town. Enfield’s High Street is this and more. While less commercial than it once was, it is still the crossroads of downtown Enfield. And it is also truly high, climbing to the top of what is known as Meat Market Hill.

High Street is also one of Enfield’s oldest streets, appearing on an early map drawn under the auspices of Enfield’s selectmen in 1806. On the map, it has no name and is just a tiny pair of lines between the “Masquema River” and two longer lines. These are marked simply as “Road” and correspond to today’s Shaker Hill Road and Route 4.

A feature near High Street on the 1806 map is “Paddleford Mill”. The Paddleford family were early settlers of Enfield, who arrived sometime after 1765 when Jonathan Paddleford purchased one thousand acres of Enfield land at a Connecticut tax sale. The family’s influence on Enfield would be extensive. Jonathan Paddleford served many times as a selectman. He also had nine children, who inherited, traded, bought and sold their father’s property over the years. In 1855 there was a Paddleford residence on High Street. Paddlefords also created the town’s oldest burying ground, which is at the north end of Oak Grove Cemetery and has been much restored.

The precise location of the Paddleford Mill is unknown; perhaps near the Enfield Public Library. In any case, the mill was the first of the industrial activities clustering around the Main Street end of High Street. This intersection was also the site of Enfield’s first bridge. Linking High Street to Shaker Hill Road, just as the Main Street bridge does today, the bridge was covered and built in 1798.

The intersection between High Street and Route 4 was once a busy street corner that hosted Enfield’s school as well as a series of enterprises and buildings. In 1845, one of these was the Farmers and Mechanics store, which also had a second floor with a large room used for meetings. Another nearby building housed a hotel and a “commodious old fashioned country tavern [that] was noted for its accommodations for man or beast, also for its good cheer both solid and fluid”.

Enfield’s Congregationalists met in the store’s upstairs room, until they purchased the tavern building. They converted this to a church and added a tower for a bell and a clock. Visible from many points around town, the church’s clock regulated the days of many Enfielders. When membership dwindled, the church was closed in 1917. After that, the building housed a Masonic temple and the Lapan family and their insurance business. In 1996 the building and other properties on this corner were taken down by the State of New Hampshire to widen Route 4 and improve the tight curve at the High Street intersection.

There was a silver lining to the building’s disappearance. The site got new life when the Veterans Memorial Park, first proposed to the Board of Selectmen by Henry Cross in 2001, was dedicated in 2003. The park commemorates the numerous Enfield residents who have fought our country’s wars, including the Revolution that gave birth to it.

Back to Top

Whitney Hall

Whitney Hall - Enfield’s 2022 town meeting is April 30th. With one of the most important items to vote on being “Library Whitney Hall renovation” (Article 7), it seems like a good occasion to provide a little historic background. As the home of the library and the town offices, the Library Memorial building has been the heart and head of our town for 120 years.

Enfield has had a library, in one form or another, since the 1850s. But it would take the building of Library Memorial Hall, as it is officially known, in 1900 to make a public, free library with a permanent building.

Enfield’s first libraries were private ones, including one formed when a successful lecture series organized by Enfield clergy raised $50 that was used to buy books for an association of around ninety members. This book collection, known as the Library Association was housed in several locations, including a dentist’s office. They were in the ladies waiting room of the railroad station in 1893, when John W. Dodge offered the town the income from $100 over ten years to purchase library books if the town would match his gift with a commitment to raise $100 for books annually. The proposal was ratified at town meeting and the members of the Library Association agreed to donate their books to Enfield’s new—free—public library. After a few more moves, in 1900 Henry Cumings offered to donate $1200 towards a permanent building for the library. A committee was formed and member George Whitney offered $100 to add a meeting hall to the proposed Library Memorial Building. E.B. Huse offered $100 to add space for the Grand Army of the Republic (the Civil War veterans’ association) and the Women’s Relief Corps.

Whitney was a prominent and generous citizen of Enfield. He was on the board of directors of several local businesses and represented the town in the state legislature. With power from the mill he owned on Baltic Street, Whitney provided Enfield with its first electricity, which was unusual in such a small New Hampshire town at the time.

When the Library Memorial Building was dedicated on April 11, 1901 it provided space for the library, a kitchen and dining room in the basement. There was also a room for the selectmen, across the hall from the library, as well as spaces for the Civil War veterans and the Women’s Relief Corps. The third floor was referred to as Whitney Hall, in recognition of George Whitney’s donation and influence. According to Enfield Town Historian, Marjorie Carr “Whitney wanted a place where people could gather and have social entertainment, etc.” and enjoy the “plays, musicals, dances, presentations” popular before television and video. The hall even served as the school gym and graduations were held in it.

The building’s stained-glass windows were given by individuals and organizations; the “G.A.R.” in the large, arched, second-floor window commemorates the Grand Army of the Republic.

Whitney Hall has remained a multi-use building, with the town offices and the Shaker Bridge Theater replacing the Civil War veterans and the Women’s Relief Corps.

During a renovation in 1976, the offices of the tax collector and the town clerk moved in. “Up until this time, those offices were in people's homes,” Carr says. As part of the general updating, the library took over the Women's Relief Corps room and acquired a vault for the historical records. However, there were no broader improvements to the library in 1976, because it was felt that their cost might keep a more significant renovation package from passing.

It is the nature of libraries and services to outgrow their spaces and for buildings to need maintenance and repair. Over the last few decades, there have been several attempts to solve the maintenance and space issues affecting the Enfield’s library and town offices.

After the 2006 Town Meeting, a Building Committee was established to research the library facilities in other towns and explore ways to improve Enfield’s facility. Based on this research, the Building Committee determined that a new library of about 7,400 square feet would meet Enfield’s needs and that the most appropriate site for it would be along the Mascoma River behind the Whitney Hall building. To raise funds, the Friends of Enfield Library was created.

At the 2007 Town Meeting, Article 11, which asked for voter approval to raise and appropriate $3.8 million to build an addition and renovate the Whitney Hall building, failed to pass. (2007 Annual Report, p. 226).

Nevertheless, at the 2008 Town Meeting, the town voted on Article 6 to establish a Library Building Capital Reserve Fund to plan, build and furnish a new, standalone library building and to appropriate funds to prepare architectural and engineering plans for it. (2008 Annual Report, p. 233) Both the Board of Selectmen and the Budget Committee recommended Article 6, which passed by a vote of 117 in favor and 45 against. With the recession of 2008 slowing the fundraising progress, plans for the new building remained on hold. (2008 Annual Report, p. 169)

In late 2015, the library’s trustees decided to move ahead with plans for the new library building and at the 2016 Town Meeting asked for permission to borrow funds to build it. Although an article was placed on the warrant to this effect, neither the Selectboard nor the Budget Committee supported the article and the Trustees withdrew the motion at Town Meeting. (2016 Annual Report, p. 213).

The coming 2022 town meeting on April 30th offers Enfield another opportunity to vote on a proposal to renovate and enlarge the Library Memorial Building. This most recent initiative grew out of the work done by the Municipal Facilities Advisory Committee (MFAC), which was created in 2019 to assess and improve Enfield’s buildings. After extensive study in Enfield and around the state, MFAC recommended renovating the existing structure housing the library and town offices building rather than building a new, free-standing one. For more details on this plan, please see the town of Enfield’s site at https://www.enfield.nh.us/home/pages/municipal-facilities-optimization-s...

From a few citizens who shared books over a hundred years ago, to the people who made 13,000 visits to Enfield’s library and checked out 30,000 items (in 2019), the Library Memorial building remains the heart and head of our town.

Back to Top

Water - Enfield's Multipurpose Gift

Water - Enfield's Multipurpose Gift - Water has been the heart of human activity in Enfield since Native American Sokoki fished from camps at the head of Mascoma Lake. Enfield’s lakes, ponds and rivers provided water to drink, food to eat and power for making things. Every day, the waters of Enfield bring relaxation and beauty to all Enfield residents.

Settlers who harnessed the Knox River to power over twenty mills in Enfield Center were the first to take advantage of Enfield water’s industrial potential.

The Shakers were also quick to put local water to use. In the summer, they rowed across the lake to sell produce to summer residents and in the winter, they transported goods over the ice. A dam on spring-fed Smith Pond powered Shaker Mills. Water from the pond was directed to Shaker fields and settlements via wooden channels and aqueducts.i The Shakers used power generated by dams on the Mascoma River for numerous enterprises, which ground grain, worked wood and wove cloth. The Mascoma River shaped Enfield’s downtown and brought other industries that depended on easy access to water, including the tannery on Main Street.

Likewise, a dam on Crystal Lake Brook (also known as Johnson Brook) spurred development in eastern Enfield’s Lockehaven area, bringing mills, shops and vacationers. The body of water known as Deep Lake, Johnson’s Pond and East Pond eventually became Crystal Lake, which along with Spectacle Pond is now a setting for both full-time and vacation homes.

Ice from Mascoma Lake was cut and sent far afield, bringing in income during lean winter months. Today, Mascoma Lake provides drinking water for the town of Lebanon.

Despite its central role in the town’s development, Enfield has not always expressed much gratitude for its lakes and rivers. In fact, we treated them downright badly for over a century.

A report of the New Hampshire Water Pollution Commission of 1954 says Enfield’s entire economy was based on industry, whose raison d’être were the area’s water resources. The Mascoma River watershed took in 30,000 gallons per day of raw sewage from the town of Enfield. The Baltic Mill dumped 5,000 gallons per day of raw sewage, plus 740,000 gallons per day of untreated textile waste.i The river below the Baltic Mill was often colored by dye wastes.

When water was low, “sewer outfalls [we]re exposed along the banks of the pond [area below the mill], gas bubbles are erupting, and an oily coat adheres to the bank vegetation. Tin cans, garbage, fluorescent tubes, burned-out light bulbs, and other refuse are, at times to be seen in this area and downstream to the Main Street dam.” Solid waste was entrapped by vegetation along the lakeshore, and around the mouths of the Mascoma and Knox Rivers, water quality was rated “Category C”—the lowest—and violated state clean-water standards. Sewage from the Knox River affected water quality at the nearby beach, popular with local residents and guests at the hotel. The 1954 report noted that a new sewer system would cost around $300,000, but that around $7,000 would make improvements.

By 1967, recreation was becoming more important to Enfield’s economy. The Baltic Mill still used immense quantities of water and dumped both chemical wastes and employee sewage into the river. Houses on Shaker Hill Rd., Pillsbury Street and Union Street sent sewage directly to a small lagoon located at the lower end of Union Street near Pillsbury Street. Sewage from Mascoma Lake houses went straight to the lake. Enfield was in clear violation of state clean water standards. State officials warned: “Unless Enfield undertakes remedial measures to clean up these lake shores and prevent the continued pollution of the water it will lose these amenities and find it most expensive in the future to regain such a natural marvel”.

After years of algal blooms and other sanitation issues, the state took action and the New Hampshire Water Supply and Pollution Control Commission (WSPCC) ordered Lebanon and Enfield to cease polluting the Connecticut and Mascoma Rivers. Study began for a combined Enfield-Lebanon sewage treatment plant; Lebanon would receive federal and state funding for the project. With the prospect of 95% funding, Enfield agreed to join in. The Baltic Mill refused to make any financial contribution, despite federal regulations calling for its participation. Then the mill closed. With one source of pollution eliminated and with a potential sanitation project that took advantage of the mill closing, Enfield declined to participate in the Lebanon treatment project.

In 1974, Smithsonian Magazine published an article about a Dartmouth College study of Lake Mascoma’s water quality problem, including how water near the head of the lake had turned “Kelly green” from algae. Would Enfield, the article asked, accept the recommendations of outside academics? The article described tensions in the town and the plight of homeowners who, instead of dumping sewage directly into the river, would have to build septic systems that cost $1,500.

In 1988, Enfield installed a sewer system, which pumps waste to Lebanon. It has been expanded twice since it was built.

Town officials and residents, the Mascoma Lake Community Association and the Crystal Lake Improvement Association, have made our town’s waters once again the center of Enfield’s economic activity—this time because they are beautiful and clean.

Special thanks to Kurt Gotthardt, who compiled a “History of the Enfield Sewer System” that is available on the town’s website (https://www.enfield.nh.us/enfield-public-library/pages/history-enfieldge...).

____________________

i Sanborn, p.114

ii Gotthardt history, p. 5

Back to Top

Know Your Heritage Commission

Know Your Heritage Commission - For the past few months, the Heritage Commission has been bringing you “Know Your Town”. But we haven’t talked about us, so this month the topic is “Know Your Heritage Commission”. When many hear the words “heritage” or “historic preservation” in their hometowns—rather than appealing vacation spots such as Charleston, S.C., Nantucket or the like—they picture “old ladies in tennis shoes” interested only in the past blocking development. As usual, reality is more complex.

Why have a heritage commission?

Preserving and respecting local heritage brings many benefits, both tangible and intangible. Connection with our heritage builds a sense of place and pride in our town’s historic achievements, which residents new and old can share and care for. It can make long-time residents proud of their town’s history. New residents who understand their new hometown’s story and values can be better neighbors and participate more effectively in town life. There are sound economic reasons to preserving natural and architectural beauty. A heritage commission and citizens dedicated to its mission pays off. Tourism is one of New Hampshire’s major businesses as well as the state’s second biggest employer. Heritage travelers tend to stay longer and spend more than other visitors.

Making heritage part of town planning has benefits for locals too. Nationwide, real estate in designated historic districts has higher values, is better maintained and sees fewer foreclosures, which contributes to economic development and increases local tax bases.

New Hampshire laws on heritage commissions

These benefits are so solid that they are encoded in New Hampshire’s law RSA 227-C. Considering that “the rapid social and economic development of contemporary society threatens the remaining vestiges of this heritage” the state declared it to be public policy and in the public interest “to engage in a comprehensive program of historic preservation to promote the use and conservation of such property for the education, inspiration, pleasure, and enrichment of the citizens of New Hampshire.”

Further consolidating this aim, New Hampshire law made heritage commissions land use boards. This put them on equal footing with zoning, planning and historic districts, which are all codified in Title LXIV “Planning and Zoning” and Chapters 673 and 674 “Land Use Boards” and “Regulatory Powers”.

Chapter 673 establishes the number of members (between three and seven), requirements for members (town residents) and alternates and relations with other municipal boards.

Chapter 674 covers the spirit and activities of heritage commissions, which are reflected in the Enfield Heritage Commission’s mission statement; to “properly recognize, protect, and promote the historic and esthetic resources that are significant to our community, be they natural, built, or cultural.” To do this, heritage commissions can receive gifts of property or money on behalf of the town. They can survey and catalog historic and cultural resources, work with planning boards and other commissions and committees, such as conservation and zoning.

Enfield’s Heritage Commission

Enfield’s Heritage Commission dates to the Enfield Village Association’s application to designate Enfield as a New Hampshire Main Street community, which required a heritage commission as a condition for Main Street status and grant money. At the 2000 town meeting, Enfield voted to create the commission and apply for Main Street designation. Since then, the commission has worked steadily to preserve Enfield’s character and buildings and improve its reputation as a good place to live and visit.

What the Heritage Commission has done for Enfield

At the 2008 Town Meeting, Enfield’s Heritage Commission members introduced the warrant article that made downtown Enfield a National Historic Register District. The district creates “economic incentives for renovation” but “impose[s] NO obligation whatsoever upon any new or existing property or upon future property owners”. Owners of buildings in the district can remodel, repaint, or even tear down their property. Being in the district does, however, give non-resident owners access to a 20% tax abatement. The article passed, making Enfield’s district of 193 properties one of the biggest in New Hampshire.

The Heritage Commission has also helped the town of Enfield manage—and save money—its own property. After the town took the 18 High Street property for non-payment of taxes, the Heritage Commission, which recognized the building’s believed historic and aesthetic value, encouraged the town to sell the ramshackle building via sealed bids that prevented demolition of the building. The eventual sale saved the town $6,000 in demolition costs, netted another $11,000 in its sale and restored a historic building to the tax rolls.

The Heritage Commission’s groundwork and negotiations with New Hampshire’s Department of Transportation made Lakeside Park possible. Without this intervention, this lot would have been sold for private homes, leaving Enfield residents with access to our town’s beautiful lake at only Shakoma Beach and the boat landing. Today, Enfield and Upper Valley citizens skate, sail and host gatherings at what is now a beautiful gateway linking historic Shaker Bridge and downtown.

Ongoing projects

The Heritage Commission’s ongoing and upcoming projects include creating a new historic area. Called the “Enfield Center Triangle” it will include the Town House, Enfield Center’s school house and the Union Church. Creating this new area could give Enfield access to grants and funding to restore the Town House from the New Hampshire Land and Community Heritage Investment Program. In addition, the Heritage Commission is seeking Certified Local Government status, which will give Enfield access to the 10% of New Hampshire’s annual appropriation for preservation that is set aside for CLGs. The Heritage Commission will also contribute its experience and expertise to the library renovation and new public safety building.

What you can do

Enfield’s Heritage Commission meets on the fourth Thursday of the month at 4:30 in the Public Works Facility at 74 Lockehaven Road. Please participate in person or via Microsoft Teams!

Back to Top

The Union Church at Enfield Center

The Union Church at Enfield Center - In the 1830s, three religious denominations in the Enfield Center community had the desire but not the finances to erect a church for their congregations. So, they joined together to raise funds for a new, shared building, which would be financed by selling pews. In this manner they raised $2,088 and sold 52 pews.

The Congregational Society acquired one-half of the church’s pews, enough to control the preaching; the Methodists owned one-quarter and the Universalists owned the remaining one-quarter. It is interesting to see such a joint effort, contrary to usual customs, made this early in history.

Building began on July 29, 1836 and the church was officially dedicated on February 16, 1837. Resident pastors conducted services and a choir sang old and established hymns.

In 1869, the building underwent some alterations and repairs. In addition to work on the cupola, subscriptions paid for a bell to be installed in the belfry and for lowering the choir loft to its current location. Upon completion of these repairs and alterations, it was decided to change the name of the church. During a regular meeting of church subscribers, Mrs. Smith Marston (whose husband had raised the subscriptions) made a motion, which was adopted by vote, to call the building the “Union Church of Enfield Center”.

The building is a rectangular gable-roofed structure with clapboard walls and a field stone and concrete block foundation. The building measures about forty-five feet wide by fifty-six feet long with the gable end facing the road and treated as the façade of the church. The center of the façade is articulated by a gable-roofed pavilion. The church is one of only a few meeting houses or religious buildings in New Hampshire that retain the form and details popular in New England in the early 1800’s.

The church seldom had a resident pastor. When available, ministers from other churches, would conduct services. Otherwise, local men would often lead the service. Once a year, subscribers held a meeting to schedule Sunday services for the coming year. Each denomination held the pulpit for a certain number of Sundays, which were scattered throughout the year. Although it was not considered necessary for one denomination to attend the services of another, attendance records suggest many parishioners regularly attended a variety of services.

On June 29, 1936, Union Church celebrated its 100th anniversary with a religious service and historical address. During the 1940s and early 1950s the parish provided an outlet for children and young adults of the community through a variety of programs. These ranged from social and recreational events to education and guidance activities.

The community again recognized a milestone in the church’s history in 1986 when it celebrated 150 years of service. In recent years the church has undergone a transformation, including restoration of the interior and the addition of facilities in the basement areas. The church family continues to offer religious guidance to a congregation today.

John P. Carr 6-2022

Back to Top

Town House

Town House - The second of the three buildings in the proposed Enfield Center Triangle Historic District is the Town House (also called the “Town Hall”). This handsome, Greek revival building on the east side of Route 4A owes its existence to the Toleration Act of 1819. Because the act mandated the separation of church and state, churches, town meetings and other government activities could no longer take place in churches.

The Town House was built by Soloman R. Godfrey in 1845. The contract for construction and site work for $739 called for a foundation of “split faced stone two feet wide and ten inches thick”, “ground dug out three feet deep under … blocking and filled with cobbled stones” as well as details about clapboards, types of nails and seating configuration.

The Greek revival style was popular with the citizens of nineteen-century New Hampshire, who saw it as a link to the ideals of ancient Greek democracy that were the model for America’s founders. The symmetrical pedimented façade facing 4A, includes a large central door and impressive, original 20-over-20 sash windows. The façade was painted white, while, to save money, the back of the building was painted in a less expensive red paint.

The Town House is not on its original site. In 1859, residents of Enfield Center and the Shakers each contested to have the building close to them. To resolve the dispute, the moderator of town meeting asked participants to vote with their feet. Those in favor of Enfield Center were instructed to gather up the road, while those in favor of Shaker settlement were to gather farther down. With more in the Enfield Center group, the building was moved to its current site on 4A—the historic Fourth New Hampshire Turnpike. To move the building, it was cut in two and the occasion was used to add a twenty-foot section in the middle. Among the movers was John P. Carr, who owned the Baker and Carr Hame Shop on the Knox River and is related to the local Enfield Carr family.

The Town House has been a hub of civic and social activity since the beginning. It was Enfield’s seat of government from 1843 to 1916, when the last town meeting was held on site. A 1909 renovation of the interior created a stage for performances and community functions. In fact, it was the site of the Old Home Days dance until 2016, when someone commented on how well the floor was “sprung”. In reality, the bounce came from support beams and structural columns that were damaged and rotting after Hurricane Irene.

In 1913, ten women from Enfield Center formed a club to “promote social and intellectual development, also to and in the support of preaching in the Union Church” known as the “Earnest Workers Club”. The Club contributed to activities at the church as well as supporting the community; buying groceries and helping families pay for dental care or making clothing for a family whose home burned. Earnest Workers’ social events, including Halloween parties and an annual quilt raffle, were held at the hall. Its membership peaked at 45 in the 1940s and in the 1980s it was disbanded (its funds donated to the Enfield Historical Society).

In the 1970s, the Town House became the new home of the Mont Calm Grange, when its building was sold. The Grange brought along its painted stage curtain, which now hangs over the Town House’s stage.

In 2016, after the Old Home Days dance, the building was closed for repairs and the floor was redone with supports. Although the building is viable, issues remain. As “an intact and distinctive example of the Greek Revival style, popular in New Hampshire between the 1830s and 1850s”, the Town House has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 2017. The town is currently applying for a New Hampshire Moose Plate grant, which would help pay for sitework to improve drainage, redirect water, and replace the current wooden steps with more authentic and safer granite ones and add wooden railings.

When this important work is finished, the Heritage Commission looks forward to the Town House’s return as a setting for Enfield social and cultural events. In the 1960s, the town of Enfield sold much of the land surrounding the building, with the result that there is no room for parking or extensive outdoor activities. Creating the Heritage Triangle is the first step in revitalizing this important building and neighborhood.

Back to Top

The Enfield Center School House

By John Carr

The Enfield Center School House - The schoolhouse at Enfield Center was born of the community’s need for larger and more convenient educational facilities for the area’s growing number of children. Constructed in 1851, it is believed to have replaced an earlier one-room school building located on Goodhue Hill; the new site offered a convenient location on the Fourth New Hampshire Turnpike, now Route 4.

The Enfield Center structure, which is a two-room type of schoolhouse, was large enough to accommodate the fifty or more pupils in Enfield Center at that time. The first class was opened for the winter term of 1851. Like most schools of the 1800s, it was not graded, with students progressing according to their speed and ability. Grading was not introduced until 1900.

In the town report of 1867, the school was referred to as “District Number 11”. The school report of 1881 said that “the schoolhouse has been repaired and supplied with the most approved furniture as evidence that the comfort and health of the pupils is of more importance to the parents than the accumulation of filthy lucre”. At a cost of $35, a cupola was added in 1900 to act as a ventilator and make the structure more attractive. Later, a bell operated by a rope threaded through the two floors was installed in the cupola; it remains there today.

Originally the school’s entrance was located in the center front of the building. Around 1908 the entrance was moved to the building’s right front corner, creating an extra-large closet for pupils to hang their outer clothing as well as shelves for book and supply storage. However, this change reduced access to the upper-level room to a single staircase. A woodshed off the downstairs entry hall had an outer wood box with a hinged cover that made it easy to pull wood through to replenish the stove.

In 1921 the schoolhouse was remodeled to conform to New Hampshire State Department plans; most of the work was of a sanitary mature. By 1941, however, there were only twenty registered students and the upstairs room was closed. In 1942, enrollment had shrunk to thirteen pupils, although it increased to twenty again in 1943.

By 1946 there were only twelve students registered for grades one through four, since the other grades had been transferred to the new village school in North Enfield. Following the fall classes of 1946, all Enfield Center pupils were transferred to the new village school

In 1947 the Earnest Workers, a women’s club, bought the building from the Town of Enfield for $500. The organization remodeled the downstairs into one large room and added a small kitchen to the back of the building. A well was dug in the yard to pipe water to the kitchen. However, the water would not pass a state water test and the kitchen pump took two pails of water just to prime. It proved easier to haul water from the neighbors!

The Earnest Workers donated the Enfield Center School building to the Enfield Historical Society, which created a museum honoring its history of education and service to the Enfield Center community.

John P Carr 6-2022

Back to Top

Huse Park

Huse Park - Many Enfield families have contributed to the town’s growth and improvement since the town’s founding. While the names of many are lost or no longer familiar, we all remember the Huse family thanks to the park named for George Huse.

George Huse was born on Shaker Hill Road in 1815 to John and Polly Currier Huse (more about the Curriers in future “Know Your Town” notes). Although it is not clear how, George and the other male Huses mentioned below, were probably related to James Huse a veteran of the American Revolution.

George was working in Canada in the lumber business when he heard the siren call of easy riches and joined the California Gold Rush of 1849.

By 1854 he was back in Enfield, married to Fanny Willis Peabody of Lebanon, and the owner of a newly built house on High Street. Described as a man of “peculiar characteristics,” George Huse died in 1897, leaving an estate of $11,000. The estate included a bequest of $500 to Oak Grove Cemetery as well as a three-acre plot of land (and money to maintain it), which is now the site of Huse Park.

In its early years, Huse’s donated land was mowed and sold for hay. In the 1970s, the park was updated with a fence, recreation building and play equipment. A memorial garden was added in the 1990s.

Near the parkland, George Huse also sold a plot to the Methodist congregation, which voted to build a church building there in 1858.

But George was not the only Huse benefactor. Everett Byron Huse and his brother John Huse were both Civil War veterans. When building a library was proposed in 1900, Everett Huse offered $100 if the new structure would provide space for the Civil War veterans’ organization, the Grand Army of the Republic, and the Women’s Relief Corps. Whitney Hall’s stained-glass windows commemorate these organizations. Jennie Huse was a librarian for many years, until she retired in 1902.

Huse businesses also contributed to Enfield economically. James Huse was involved in one of Enfield’s most enduring businesses, the “bedstead shop.” It started out making bedsteads in a mill on the Knox River in Enfield Center in the 1840s. When dams improved the Mascoma River, bedstead production moved into a new facility in the Baltic Street area, which James Huse and a partner leased. Huse would go on to various partners and shareholders, but the shop stayed in the Baltic Street area and eventually employed up to 20 people. Business declined and Huse shut it down in 1882; in 1897 the building housing burned.

The decline of the business and fire were accompanied by another loss in 1898. Bertha Huse was reported missing. Huse, who was thirty-one, never married and “noticeably despondent.” A diver was brought in from Boston to search among the log pilings of Shaker Bridge, where it was feared Huse had jumped to her death.

Crowds lined the bridge to watch the diver’s fruitless search for Huse among the tangle of logs. Several days later, Mrs. George Titus of Lebanon, who was reputed to have psychic gifts, stood on the bridge and pointed to the water below. “She is down there,” Titus said. This time the diver found Huse’s body. Bertha Huse was buried in Oak Grove Cemetery.

Back to Top

Follow up on Old Home Days and Certified Local Government

Follow up on Old Home Days and Certified Local Government - During Old Home Days, members of the Heritage Commission, the Enfield Historical Society and Union Church hosted dozens of visitors to the three buildings in the Enfield Center Historic Triangle; the School House, Union Church and the Town House.

Visitors admired the lovely spaces, the handsome architectural details and insights into Enfield’s past. “Wow, I didn’t know this was here!” or “What a beautiful setting this would be for a wedding/event/meeting”.

Almost every exclamation of admiration was followed with questions about how we can use these beautiful buildings better.

The best answers came from visitors themselves. They suggested them as settings for local arts events or weddings and other festivities. They could be spaces for classes or meetings or homes for local groups. All of these suggestions could not only revitalize these buildings, but also bring our town together and attract interest and investment from outside.

Of course, it’s never simple. These buildings are old. They have issues, such as parking, accessibility, no sanitary facilities or heating/cooling.

Help is available. Both the state of New Hampshire and the federal government offer programs that can contribute to getting value from Enfield Center’s treasures.

Such help comes in the form of training, planning grants or capital grants, from $50,000 to $250,000 in the case of the Sacred Places initiative. Other help comes from tax credits, such as the Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentives Program’s 20% investment tax credit, awarded to rehabilitate historic buildings that can then produce income.

Applying for these grants is time consuming and delicate. Enfield can and has competed successfully for some of this aid. A Land & Community Heritage Investment Program (LCHIP) grant aided the Smith Pond/Shaker Forest project. Two Mooseplate grants repaired the Town House’s floor and support beams. Competition for such grants is stiff. Only recently the Heritage Commission’s application for another Mooseplate grant to replace the Town House stairs was not successful.

One way to improve Enfield’s chances is to join the Certified Local Government Program (CLG). This is “a partnership between municipal governments and the state historic preservation program, to encourage and expand local involvement in preservation-related activities.” Becoming a Certified Local Government would give Enfield access to between $50 and $150 million that the federal government provides for historic preservation. At the moment, this largesse ends up in certified local government towns such as our Upper Valley neighbors Lebanon and Claremont or the cities of Nashua or Manchester.

The first—and key—step that Enfield must take for certification is to designate a Local Historic District. In our case, this would be the Enfield Center Triangle; the School House, Union Church and the Town House. No other buildings in Enfield Center are affected.

The regulations for such historic districts are created by the towns themselves—not the state or the federal government. There is great leeway. For example, the Heritage Commission has been looking at Bristol’s rules as a model. Bristol allows additions and renovations to buildings and concessions to modern life, such as non-wood siding or air conditioning in its historic district. Even demolition is possible. The goal of a historic district is to encourage thoughtful change in the district, not create a costly time capsule of buildings.

In a few days, Enfield’s new master plan will be published. Its second guiding principle is to “honor our unique history through purposeful preservation.” Heritage is part of Enfield’s unique brand. It can bring in new resources and residents and improve the services and opportunities that residents asked the Planning Board to deliver.

Keep your eyes peeled and lend your support as the steps for certification go through the town legislative process with hearings about historic district regulations and warrant articles. Make a difference!

For more information, see the New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources. Summary of state and federal programs for historic preservation

Certified Local Government Program (CLG)

The CLG program encourages and expands local involvement in preservation-related activities.

Conservation License Plate Grant Program - Moose Plate Grants

Grants for the conservation and preservation of significant, New Hampshire, publicly owned historic resources or artifacts.

Land & Community Heritage Investment Program (LCHIP)

Makes matching grants to New Hampshire communities and non-profits to conserve and preserve New Hampshire natural, cultural and historic resources.

NH Preservation Alliance - Community Landmarks and Grants

This organization helps New Hampshire individuals and communities achieve their preservation goals with education and funds

National Trust for Historic Preservation - Preservation Funding

Grants that help nonprofit organizations and municipalities gain technical expertise and find and encourage financial support from private and nonprofit sectors.

National Fund for Sacred Places

Partners for Sacred Places and the National Trust for Historic Preservation provide grant funding to strengthen the sacred places of all faiths in communities.

Back to Top

Enfield’s Fire Department

Sanborn, pp.231.